National Archives Who Built the National Museum of African Art

We desire to bear witness the rich creative heritage of Africa, and to underscore the implications of this heritage in America's quest for interracial agreement. We want to exist a museum that communicates.

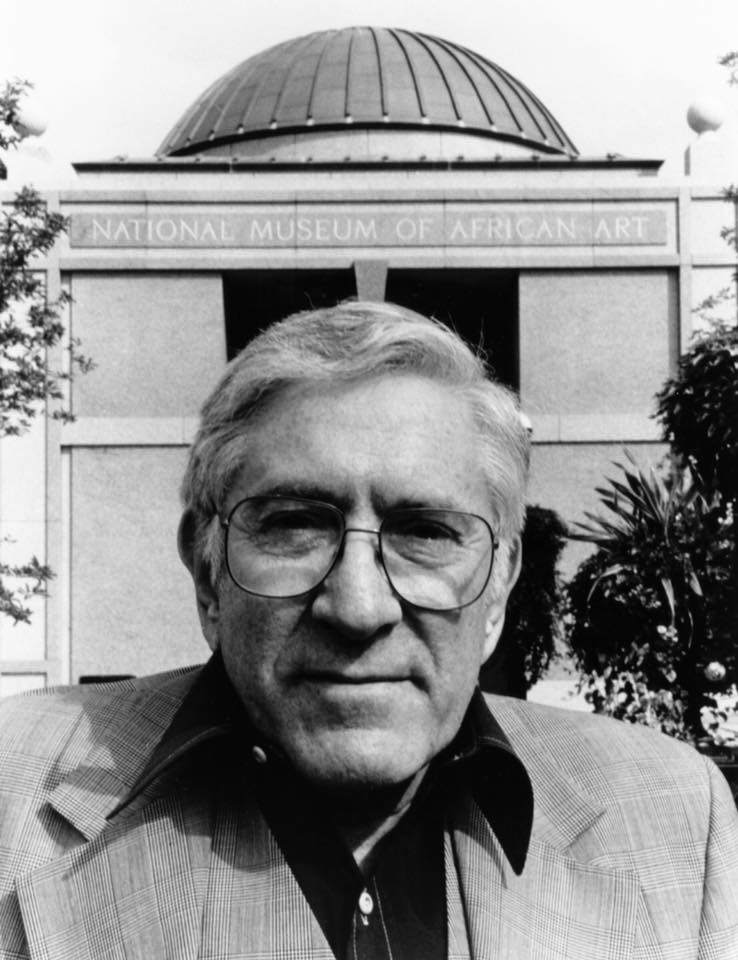

Warren Murray Robbins

Warren Murray Robbins (1923–2008) was not immensely wealthy, had not been to Africa, and had no experience running museums or formal training in fine art history prior to the 1960s. Nonetheless, in 1964, by leveraging his diplomatic experience and passion for African art and culture, he founded the Museum of African Fine art, which he initially privately managed as he sought additional funding. In 1966, the museum established the Frederick Douglass Institute of Negro Arts and History, the museum's educational arm. Both the museum and the institute were housed in Northeast Washington, D.C., in a townhouse that had been the home of the abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass in the 1870s.David A. Binkley et al., "Building a National Drove of African Art: The Life History of a Museum," in Representing Africa in American Art Collections: A Century of Collecting and Brandish, ed. Kathleen Bickford Berzock, and Christa Clarke (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011), 265. When the collection became function of the Smithsonian Institution in 1979, it was renamed the National Museum of African Art. Robbins was its first director until 1983.

Robbins was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, on September 4, 1923, the youngest of xi children born to Jewish immigrants from Ukraine. As an adult, he explained that his Jewish identity allowed him to relate to the struggle for civil rights in America, based on "the historical ties between the Jewish and Black people in their common centuries-long quest for justice."Warren M. Robbins, Speaking of Introductions: Vignettes of a Cultural Pioneer; A Journey through 4 Careers and Iii Continents (Washington, D.C.: Robbins Middle for Cross Cultural Communication, 2005), 56.

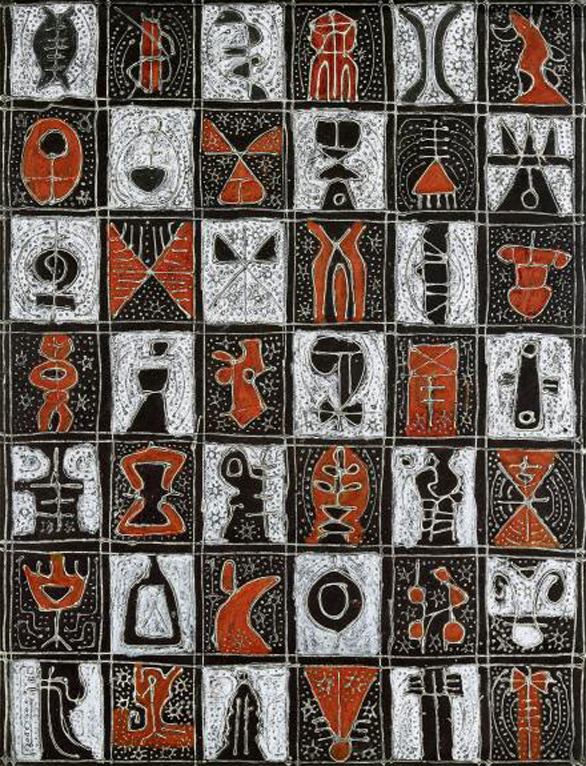

During his childhood, he became fascinated by the geometric shapes of the tiling in the family unit bathroom. He ascribed his afterward appreciation for the piece of work of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian to this initial contact with the tile shapes. His honey for some designs in African fine art also grew out of this love for geometric shapes; he after wrote: "I was instantaneously attracted to the blackness and white checkerboard patterns of certain African textiles from Mali or the painted superstructures of heraldic masks from Upper Volta."Robbins, Speaking of Introductions, vi. Indeed, Robbins's adoration for both Western modern fine art and African art forms motivated him to demonstrate the connections between the two; he would later on argue for the influence of African sculptural forms on the paintings of Picasso.Robbins, Speaking of Introductions, 24. His dwelling house on Capitol Colina featured a gallery in which he displayed Mondrian's work alongside traditional African sculptures. Robbins, Speaking of Introductions, seven.

Collector's Adult Life

In the 1950s and 1960s, Robbins worked in Frg and Austria every bit a diplomat and teacher, gaining feel in cross-cultural relations.Robbins,Speaking of Introductions, 238. His connections to the Foreign Service later on proved helpful for increasing the drove of the museum, equally it received gifts from collectors and American officials stationed in Africa. These gifts included several objects that were non commonly collected at the time and contributed to the eclectic nature of the collection.

In Deutschland, Robbins'due south interest in African art was profoundly heightened by Life mag photographer Eliot Elisofon's 1962 book, The Sculpture of Africa. At that time, Robbins described it as "the most all-encompassing and well-nigh important photograph survey of African art that had ever been published."Robbins, Speaking of Introductions, 73. Elisofon would afterwards leave his vast collection of photographs to the museum. Robbins would later publish his own book, African Art in American Collections, in 1966.Philip Stanford, "Love Not All Requited: Warren Robbins and the Museum of African Fine art," Washington Post, March 9, 1969.

The Museum at the Frederick Douglass Business firm (1963–1979)

Robbins began to develop the thought for an African art museum while he was working in Germany.Stanford, "Love Non All Requited." He resigned from the Land Department in 1962 and, one year afterwards, founded the Middle for Cantankerous-Cultural Advice in Washington, D.C. Its get-go major projection was to raise funds to open up a museum of African art.Stephen Rosoff, "The Collector," Michigan Alumnus (January/February 1992): 28. Robbins "bought a second-hand IBM,"Stanford, "Love Not All Requited." hired a small staff, and worked out of his basement, making calls and writing to potential patrons. In 1964, he took out a mortgage to purchase the former dwelling house of Frederick Douglass, located backside the Supreme Court building, and established the Frederick Douglass Found of Negro Arts and History, which was dedicated on September 21. The museum and institute had the mission of sponsoring exhibits and lectures on the contributions of African and African American people in the Us.Penelope Lemov and Gail Werner, "African Art Museum and Douglass Constitute Are Booming," New York Times, June 29, 1969; Eden Orelove, "Happy Birthday Frederick Douglass!: A Commemorative Web log from the National Museum of African Fine art," Smithsonian Collections Blog, February 14, 2008, https://si-siris.blogspot.com/2018/02/happy-birthday-frederick-douglass.html.

Robbins did not work lonely. He used his diplomatic feel and personal network of artists, politicians, and collectors to elevate the stature of the museum. Its first board members included Frances Humphrey Howard, sis of Vice President Hubert Humphrey; the writers Ralph Ellison and Saul Blare; Senator S. I. Hayakawa, whom Robbins had met during his time as a diplomat; and Robbins's commencement cousin, the announcer and media personality Mike Wallace.Rosoff, "Collector," 28. Hubert Humphrey, the lead writer of the Civil Rights Human action of 1964, would later be instrumental in helping the museum become part of the Smithsonian Institution by an deed of Congress in August 1979.Robbins, Speaking of Introductions, 99.

Robbins wrote about his principal goals for the museum in a 1969 article: "We want to show the rich creative heritage of Africa, and to underscore the implications of this heritage in America'southward quest for interracial understanding. We want to be a museum that communicates."Quoted in Binkley et al, "Building a National Collection," 265. He stated his belief that "the widespread myth that the Negro American has no by other than slavery and savagery has constituted one of the most tragic and unnecessary stumbling blocks to his thinking about himself . . . [and] a source of racial prejudice."Benji J. O. Anosike, "Africa and Afro-Americans: The Bases for Greater Understanding and Solidarity," Journal of Negro Education 51, no. 4 (1982): 434.

To that end, he set out to make the museum a symbol of black cultural pride and a tool to educate people about African art. The staff were members of the local community with varying degrees of familiarity with art history and museums.Binkley et al., "Edifice a National Collection," 266. Ric Simmons, the museum's holding manager in the 1970s, recalls that "the place was part of the customs" and that Robbins hired people "to bring African Art to life."Richard, "Double Vision." At that place was meaning engagement from the black community. The Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes sent his poem "Frederick Douglass" to Robbins to be used every bit a argument for the museum.Robbins, Speaking of Introductions, 103.

Robbins envisioned the Frederick Douglass Institute of Negro Arts and History/Museum of African Fine art every bit not merely an art museum, simply as an educational establishment.Robbins, Speaking of Introductions, 187. In the early years, many visitors were school children and, by 1978, the museum had refurbished a school coach for educational trips.Binkley et al., "Edifice a National Collection," 268. Robbins afterwards stated that "the museum was no Disneyland, but children came away from it with a positive feeling about an Africa to which for the beginning time they could chronicle."Warren 1000. Robbins, "Two Visions for African Fine art," Washington Mail service, January 26, 1997, http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/1451851739?accountid=11311.

The public did not unanimously accept Robbins'due south involvement in the creation of an African fine art museum, with some criticizing his "handling black culture" with a "colonial mentality." He responded to objections, stating, "I'grand not doing this equally a white person, but equally a sponsor of an establishment the city needs."Stanford, "Love Not All Requited." Despite these criticisms, big numbers of people continued to visit, and information technology remained the only museum dedicated solely to African art at the time.Lemov and Werner, "African Art Museum." Noted philanthropists in Washington, D.C., as well supported the museum. In 1970, David Lloyd Kreeger, the philanthropist and art collector, donated coin for a large-scale expansion of the museum, which the blackness architect Robert Nash was commissioned to complete.Bart Barnes, "Architect Robert Johnson Nash, 70; Designed Churches, Public Buildings," Washington Post, Dec nine, 1999, https://world wide web.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1999/12/09/builder-robert-johnson-nash-70/8538472a-8042-42e6-b42f-6ade441ea5ae/?utm_term=.c89f79b2980c.

Despite Robbins'southward comparative lack of wealth and formal grooming, the Frederick Douglass Found/Museum of African Art grew to occupy eight next townhouses and to take a collection of over five thou works.Interview with Christine Kreamer, Deputy Managing director and Master Curator, National Museum of African Fine art, Smithsonian Institution, past Mofeyifoluwa Edun, Jan 11, 2018. Before joining the Smithsonian, the museum had a 30-five-person staff and a flexible administrative construction comprising an advisory board that included Saul Bellow, D.C. mayor Walter Washington, and Eliot Elisofon.Rosoff, "Collector," xxx; Binkley et al., "Building a National Collection," 266. Robbins spent much of his ain savings establishing the museum, but he eventually raised $v.5 million, allowing the museum to run on an operating budget of $800,000.Stanford, "Love Not All Requited"; Rosoff, "Collector," 30. Some of this coin came from foundations, such every bit the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations.Stanford, "Love Non All Requited." In 1969, the museum also received a bequest of African art from Mildred Barnes Bliss, who, along with her husband, Robert Woods Bliss, had founded the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.Binkley et al. "Building a National Collection," 267.

Joining the Smithsonian

Equally the museum grew, Robbins sought to ensure its longevity. In 1974, Robbins proposed that the museum become part of the Smithsonian Institution, believing that such a move would provide admission to the resource information technology needed to become a preeminent institution for the study of African fine art.Binkley et al., "Building a National Collection," 269. This was at a time when the Smithsonian was also absorbing institutions such as the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

Robbins'due south museum was made office of the Smithsonian in 1979 and was renamed the National Museum of African Art in 1981."National Museum of African Art," Smithsonian Establishment Archives, April xiv, 2011, https://siarchives.si.edu/history/national-museum-african-art. The new location on the National Mall opened to the public on September 28, 1987.Binkley et al., "Building a National Collection," 269. Compared to the $5.v million Robbins had been able to raise for the Frederick Douglass Institute/Museum of African Art, the new edifice cost $73 million and had v times the exhibition infinite.Michael Brenson, "Beneath Smithsonian, Debut for 2 Museums," New York Times, September viii, 1987, http://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/08/arts/beneath-smithsonian-debut-for-two-museums.html?pagewanted=all. The Smithsonian funding immune the museum to pursue more ambitious exhibitions, learn rare and unique works, and absorb major private collections, including an of import collection of ceramics from key Africa.Binkley et al., "Building a National Collection," 271. In the end, however, Robbins was disappointed in the "unselfconscious elitism" he saw creeping in.Robbins, "Two Visions for African Art." The museum, he felt, had "lost its soul."Richard, "Double Vision."

It was every bit a part of the Smithsonian that the museum outset developed clear institutional guidelines for collecting modern and contemporary African art. This institutional directive helped to set the museum upwardly to get one of the foremost museums of contemporary African art, as well as one of few museums that exhibit both traditional and contemporary African art.Binkley et al., "Building a National Drove," 275.

Notwithstanding, the Smithsonian museum also continued traditions initially established past Robbins. These included the "focus gallery" approach, encouraging visitors to engage deeply with one particular work, and the "comparative gallery" arroyo, showcasing the influence of African art forms on Western art movements.Binkley et al., "Building a National Collection," 273. One exhibition curated by Lydia Pucinelli, who would later get Robbins's wife,Joe Holley, "Museum of African Art Founder Warren Robbins [Correction 12/22/08]," Washington Post, Dec 5, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/12/04/AR2008120404003_2.html. used the article of furniture of Pierre-Emile LeGrain to demonstrate the significant influence of African forms and patterns on the Fine art Deco movement.Binkley et al., "Building a National Drove," 273. The new museum as well continued to pursue Robbins's goal of demonstrating the influence of African culture on the Western world and is credited with being ane of the first U.Southward. fine art museums to get-go a diversity initiative."Fostering Multifariousness in Art," Smithsonian Campaign, National Museum of African Art, accessed February 23, 2018, https://smithsoniancampaign.org/unit of measurement/national-museum-african-art?Select-Unit=87; "Johnnetta Betsch Cole Fund for the Time to come," National Museum of African Art, accessed February 3, 2018, https://africa.si.edu/back up/jbc-fund-for-the-future/.

Conclusion

Warren M. Robbins created the nation'south start African art museum not only to showcase African artworks, only also "to foster cantankerous cultural communications betwixt people through didactics in the arts of Africa.""A Personal Invitation from NMAfA Managing director Johnnetta B. Cole," National Museum of African Art, May 21, 2014, https://africa.si.edu/2014/05/a-personal-invitation-from-nmafa-director-johnnetta-b-cole/. He thereby created an establishment that was both a public art museum and an educational eye that helped to further interracial understanding in America. Today, the National Museum of African Fine art distinguishes itself as the first museum in the United States to include in its mission a sustained focus on both traditional and contemporary African art. And as a direct consequence of Robbins's vision and the Smithsonian's stewardship of both his museum and his educational outreach and public programs, the museum has expanded the parameters of African art history and preserved for the public good the rich variety of African artistic and cultural traditions.

Contour by Mofeyifoluwa Edun, 2018 Wintersession student, and Faye Yan Zhang, 2017–2018 Dumbarton Oaks Humanities Young man.

Source: https://www.doaks.org/resources/cultural-philanthropy/national-museum-of-african-art

0 Response to "National Archives Who Built the National Museum of African Art"

Post a Comment